A Story of Clay, A Tale of Butterflies

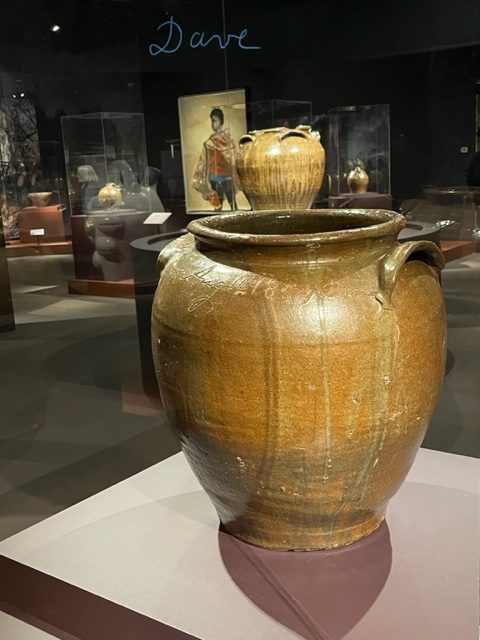

David Drake stood out.

Not only was he a master potter. He was a literate slave – a person so rare as to be a living miracle — working in western South Carolina in the 1830s.

How this came about remains a mystery. Call it grace or the benevolence of someone from the great house. Or perhaps it was expedient: a slave who could conduct rudimentary business over the collection and management of the clay, the writing of orders, the shipment of pots, was a useful commodity.

It is enough to stop the heart, however, when you stand before one of his massive vessels today and see what Drake did with his extraordinary gifts: he inscribed poetry and prayers into the wet clay before setting it in the kiln to be fired.

Drake’s vessels, and those of other gifted Edgefield, SC, potters, survived the Civil War, Reconstruction, and almost two centuries of hope and the crushing relentlessness of racism in the American South. They are now valued at upwards of $1.5 million at auction houses, and are touring art museums around the country.

We look to our poets and painters, our pot-makers and our weavers, to affirm our deepest intuition: that we are here to evolve from creatures absorbed in the business of our own survival, to something altogether different.

The great stories of myth speak to this transformation, a turning to our essence, our best selves. And those who carry these stories forward speak of the daily practices that encourage transformation to happen, even in the midst of history’s (and personal) horrors.

Slaves produced most things on southern plantations, and the enslaved potters of western South Carolina were well-known for their skill and acumen with the local clay. For some, like Drake, the daily disciplines and rhythms of the work must have come to have a potential far beyond the goal of providing his white masters with storage for food.

The pots became his testimony, his legacy, his “books,” preserving for history his lamentations, his pleadings, and his trenchant, stirring, truth-telling about his condition in life.

.His pots are radiant artifacts of transformation – clay to vessel, literacy to soul expression, functionality to invention. As I stand before them, pondering the ways of transformation, I wonder what Drake, if he were here today, would say about the ways in which the clay and his intelligence shaped him, every bit as much as he shaped them.

This is a crucial teaching: the materials we work with become our intimate partners on our life’s journey. It matters how we use them. We can view them as means to an end. Or we can choose to let them transform us – be they ideas, words, vegetables, clay, threads, sorrow or joy. Every craftsperson worth their trade knows that “mastery” means dialogue, not overpowering

Drake left behind a legacy of embodied light, a creativity of life. We see the same shining out from so many of the artifacts that have survived from marginal makers: Amish quilts, folk diaries, tribal masks, Inuit carvings. Tellingly, these pieces often aren’t signed, the ultimate testimony to the non-egoic nature of the transformation of which I write.

These objects affirm our deep intuition that we are each meant to transform the raw materials of our lives into something of beauty, power and grace. We don’t lack for instruction, but we often want the focus necessary to follow through. It is often only when our cocoons of achievement, acquisition, and power (or, the lack of these) are exposed as too thin to substitute for real meaning that we begin the journey to become the artists of life that we are meant to be.

In our times, when we have so privileged technological knowledge and its tools that its lexicon is replacing words describing nature from our dictionaries, when many children have almost criminally reduced exposure to both nature and arts and crafts, we might do well to ask: Who will write our poems and create our quilts and tend our gardens, if we fail to pass along these most meaningful avenues of transformation? Who will be the future witnesses of transformation?

It is up to us to share these stories, and to study them for our own transformation.

Easter is coming. Tombs are opening. People are speaking in tongues.

(https://mfa.org/exhibition/hear-me-now-the-black-potters-of-old-edgefield-south-carolina)

Katherine Hughes

April 8, 2023at7:37 amYes! Thank you!

Barbara McEvoy

April 6, 2023at9:16 amThank you,Kathleen. and thank you for including the links to MFA’s exhibit…Between your essay and MFA’s photos and short videos this was a touching experience, Seeing his and other slave works, then watching the videos was indeed inspiring. As Dave’s descendents emphasized, we don’t know who will see our own works, but that shouldn’t stop us from revealing our souls in even our “marginal makings.” I especially liked your next to last paragraph.

Kathleen Hirsch

April 7, 2023at7:24 amYes, Barbara, our “makings” enrich the life around us, even if they don’t make us “famous” in any traditional sense of the word. It’s all good.