Of Broken Knees and Mending Hearts

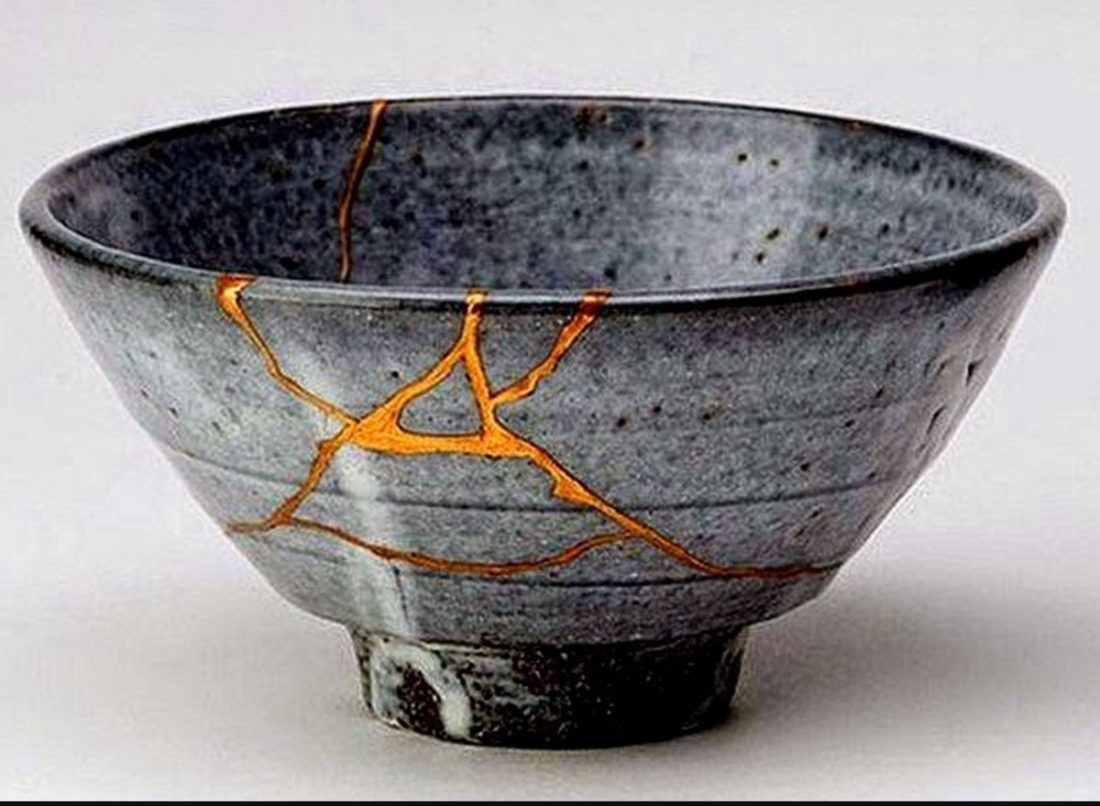

Healing is the art of skillful means. The Japanese long ago invented Kintsugi, the art form that reassembles broken pots by soldering precious metals — gold and silver — between the pieces.

The new object is complex and compelling, a meeting of accident and artful reconstruction.

Western art offers its own examples of transformative beauty. Collage. Quilts.

And isn’t Scripture itself similarly a patchwork of narrative, forged together in the struggle to wrest meaning from life’s pain and chaos?

The work of patching has had a particular urgency for me this past month. During this time, I have been devoted to helping my husband mend from three sequential surgeries, lingering infections, and a shattered web of tendons in his left knee.

If there has been a gift in this, it is that I have been made keenly aware of the ways in which I am bound to hundreds of thousands wounded by COVID, or who have seen their social and political worlds shattered, or by those who bear the keenest brunt of our natural world presenting us with the past-due bill for our neglect, abuse, and consumption.

This time of intense focus on needs physical, emotional, and spiritual has deeply fed my understanding of healing, whether of loved ones, the people I see in spiritual direction, or in my larger communities.

The first thing that I have learned is that healing is never abstract. It is deeply particular. We can only heal one person, one piece of the earth. We can only bathe, dress, and feed a very few in our orbit, and even for this if we can manage it we need help: other people, financial reserves, time to rest from the exhaustion of constant care, time to pray and restore our faith and perspective.

This leads to the second thing I have learned, again, about healing. Stripped to its essence, healing is an invisible process, a struggle between hope and despair.

To anyone whose life has ben unexpectedly and radically disrupted, frustration, malaise, exhaustion eventually knock on the door, uninvited visitors who don’t easily depart. We have to learn all over again that good behavior doesn’t “save” us. That we are powerless. Despair can take up lodgings in us, leave the pot broken, grieve its destruction, obsess about the reasons it broke in the first place. It rejects the worn garment, and in its little cave at the center of one’s heart, easily turn to substitutes — anger, distractions, addiction — the deadening of feelings.

My husband’s accident was a traumatic event, in the immediate aftermath of which survival instincts took over. Hypervigilance, the near-obsessive concern for safety, cleanliness, orderly medications, food, bodily functions. These occupied the first several weeks, as he became familiar with new ways of using his good leg, relying on devices for support, practiced his breathing, and tried to get enough sleep.

The events that led to the accident were told and retold, as is necessary in any traumatic event. Medical and PT people came and went, shared the story and added their observations and advice. Friends and family weighed in, came to help, sent cards, made phone calls. Together, we created a narrative, which like all stories had movement and new, gradually unfoldings: benchmark advances, minor setbacks, goals created and reached and surpassed. The hero’s journey of fairy tales has nothing on the real narratives of healing.

But then comes the middle phase of the healing journey. It comes to us all on the journey of life, and to anyone on the healing journey: in broken knees and in therapy and in spiritual direction. Survival is no longer at stake. The slog begins. Progress is slow, improvements infinitesimal. Boredom sets in, or disillusion, as the novelty of the situation wears thin. The same sitting positions, the same views out the same windows, the same absence of a miracle. With the outward structures of this incubation time in place, the narrative turns inward.

This is where the struggle between despair and hope begins to play out in earnest. It is where all of us who care about our world must learn to pay close and discerning attention.

People who are hurt suffer waves of PTSD, negative self-talk, impatience, ebbing resilience, fatigue. They fall prey to hidden, destructive temptations, among them, learned helplessness, resistance to change (necessary as it is), accidie, going in circles.

I recently stumbled upon old notes of Richard Rohr’s book Hope Against Darkness. It has much to recommend a rereading. In it, he diagnoses the origins of our current state of social despair in the erosion of a meaningful worldview (which he refers to as a cosmology) that offers a vision of the soul’s progress, of maturing consciousness, and images of human wholeness. We have substituted the toys and arguments of modernism, elevated ourselves as the “gods” of our existence, and inevitably, as we fall from our pedestals, have tumbled into cynicism, nihilism, and what he calls “the embittering wound.” Lacking any guidance on the problem of pain, he argues, we are driven to false solutions to our brokenness – materialism, circular self-absorption, fragmentation.

But when he says that the challenges of healing this despair requires “unbounded enthusiasm and confidence,” I part ways with him.

In my experience of working with wounds, recent and otherwise, what is needed to rebirth hope is quite other than “unbounded enthusiasm.” Rather, those of us who would try to be healers need to a capacity to listen “through” the other — through those who are hurting — in order to hear or see the next necessary step in the journey. And to do this consistently, we need to dig deep into our own wells of patience, and perseverance, and visions of wholeness.

Rather than being “fixers,” we need to be witnesses, intuitives, trusting that the unique arrangements of clay shards, the assemblage of scrap fabric, will create a new whole that embodies the authenticity of the person, or community, who seeks restoration. We need to be story tellers, sharing those archetypal tales and images of the journey from passion to compassion, from ego to a higher definition of the self.

As a wise man recently said to me, the aim isn’t perfection, but growth, into wholeness.

Hope doesn’t lie in the eradication of our shadows, any more than it does in the elimination of our surface scars. These, like the Japanese pots, tell the story of a second life, one that only emerges through the shattering of the first.

The stretching, patching, making do with the materials at hand — and the imaginative leap out of which new arrangements and visions of wholeness emerge — is our best template for healing our damaged bodies, our wounded souls, our fractured worlds. It is always small, personal, and true to the ecology of the original.

The other day, for instance, my husband dropped his second crutch, and began to walk with one. Progress suddenly accelerated. He cooked a meal at the stove. He even did the dishes!

He is still very cautious, reluctant to tackle certain physical challenges, but the dishes were to this fellow-traveler, a sign of hope indeed!

Katherine Hughes

April 7, 2023at8:02 pmKathleen, I’m so sorry – we did not know Mark had been injured. We send you both our love and prayers for continued healing.

Kathleen Hirsch

April 7, 2023at9:03 pmKatherine, somehow this old post was reposted! Mark had a bad knee accident in 2021. He is almost fully recovered, but it’s been a journey. Thank you for your concern and friendship, as ever.

Ann Lafferty

April 7, 2023at12:46 pmYour story today, reconnects me with mine, via loss, PTSD, patching together clay, fabric, quilts, and paintings, and of course the spiritual side of the healing process. Soon, I will try to share my story and some images with you.

Kathleen Hirsch

April 7, 2023at9:03 pmThank you, Ann. Good to hear from you.

Elizabeth A Rhymer

October 1, 2021at6:39 pmA sign of hope indeed!

Barbara McEvoy

September 25, 2021at1:57 pmWonderful…didn’t know about Kintsugi, but a beautiful image for so many aspects of life…