The Passion of Frida Kahlo

Images of torture devices hung on the walls before me. Stained, twisted restraints, antiquated and painful protheses, chipped cups tied to a wall.

What had I walked into on a Sunday afternoon at the museum?

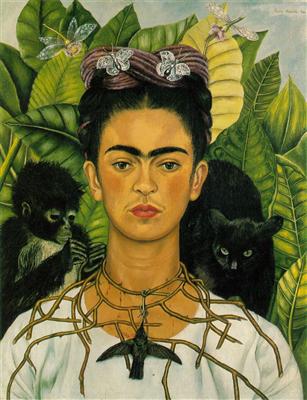

Moments before, I had been standing in galleries vibrant with color. I wanted nothing more than to return to them, to the fiery genius of Frida Kahlo, her flouncy skirts and magical, primitive paintings, surrounded in the display by the folk pots and weavings that inspired her work.

The small exhibit at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts was a revelation of the redemptive possibilities of art in a culture shattered by war, division, and ideological polarization.

Kahlo was part of a group of artists who emerged at the end of the Mexican Civil War, a conflict that tore the roots of the existing order at its point of greatest tension — the influence of the Conquistador heirs pitted against those of the indigenous peoples; between folk traditions and an imposed Catholic faith, rituals and iconographies. Beneath the surface inequities of power and wealth lay the deeper lacerations of displaced identity and cultural imperialism.

At its heart, that was asking: Who are we as a culture? What are our real sources of power? What expresses our values? Gives us hope?

By 1920 Mexico was in tatters, reduced to psychic and physical rubble.

Kahlo and others became the gleaners among that rubble, seeking the shards that could be restored. From the small folk pottery shops, the weavers and embroiderers who survived, they raised up the objects they believed expressed the true spirit of their broken world.

We owe many of our images of Mexican culture — the bold cloths with their ocean blues and sweet pepper reds and oranges, the peasant skirts and ropes of papier mache vegetables, retablos and fantastical creatures, the Alebrijes — to Kahlo, her husband, Diego Rivera, and their circle.

As I turned to leave the chamber of horrors, for the galleries that were such a feast to spirit and eye, I paused to read the description of the sad photographs.

And in that cold, dark place, the light suddenly pierced me. I was standing in the cave of Kahlo’s suffering.

These were images of the devices that she donned each day to stabilize her spine and limbs after a crippling accident as a medical student that doomed her to a succession of unsuccessful surgeries, and a broken body that eventually took her life. Beneath her colorful skirts and distracting jewelry, beneath her bright personal surfaces, was chronic pain. These devices enabled her to manage so that her soul could soar in her art — precisely as her art enabled her country to soar from the crippling aftermath of civil war.

This room was the recorded of Kahlo’s private martyrdom, her solitary suffering. These were the first realities to which she woke each day and the last she removed as she prepared for sleep — harsh bookends of days spent in the presence of her inner transformative spirit.

Without each other, these two exhibits would have been woefully incomplete. Together, they revealed in a wholly new way the power of the wound, that both sets each of us apart and can became the fire of our transformation.

When suffering arrives, when life as we know it has died – our hopes, our health, the security of our home life, our peace of mind — we have the same choices that Kahlo had. We can flee, or we can become the artists of our own lives – excavating hope and new life from pain and rubble. Passion requires that we stretch ourselves beyond suffering to the power in us that is greater.

Nothing in the harsh afterlife of Kahlo’s suffering belie the difficulties of this choice.

Nothing in the rooms of her transcendent imagination can challenge its triumph.

Nancy rappaport

April 20, 2019at5:41 pmJust came back from Fridhaexhibit inspired to go by your post . I love the twist she makes on ex Voto and how she saved a child bank that the only way to get the money was to break the ceramic horse . The intimate pictures of her bathroom preserved/ fortified and the unveiled for us I found particularly poignant to see her braces and her hospital smock which you couldn’t tell if it was blood or paint drops . To healing and renewal and the blessed determination she showed to create !

kathleen.hirsch

May 6, 2019at8:26 amNancy, I thought I’d replied to this, but see I had not. Yes, indeed — to healing and renewal, to shape-shifting and creating new realities from out of the most profound brokenness. A lesson for the ages.

Nancy rappaport

April 13, 2019at7:20 amWhat an amazing thoughtful piece. I am sitting in a hotel in nyc with my oldest daughter Lila after her trying on her wedding dress.. fridas pictures of when she had miscarriage are so haunting to be deprived of the joy of creating a family larger than Diego. But she poured generativity into her work. We went to Mexico City and saw her house and also Diego and her house . Her house tour besides having cult like status and with that crowds the sense of her spirt was palpable. Down to the urn next to her bedroom which had her ashes and her braided. Hair. The only aspect I would question is she may have elevated healed a broken country but I also don’t want us to overlook that Mexico is a vibrant country and Mexico City has deep layers of persistence which a civil war, corruption “lacerations” still imbues fortitude !

Thank you ! Off to soul cycle . Nancy

kathleen.hirsch

April 13, 2019at7:23 amThank you for this, Nancy! I completely agree about Mexico’s vibrancy. I think that she and Diego were major contributors, and “midwives” as well!

Enjoy wedding preparations!